Deanne Rogers: Hyperspectral Imager

Deanne Rogers may be an expert on the surface of the Moon and Mars – though she’s never been to Mars or to the Moon, for that matter.

But the work that the Stony Brook University geologist took on in April 2022 – perched in a volcanic field in New Mexico with a machine that analyzes the composition of rocks – may help astronauts get back to the Moon and, eventually, to the red planet.

“It's all about, for me, just doing good work,” she said during a break in the RISE2 expedition to the Potrillo Volcanic Field in New Mexico. “Keep your head down, do good work.”

That she did.

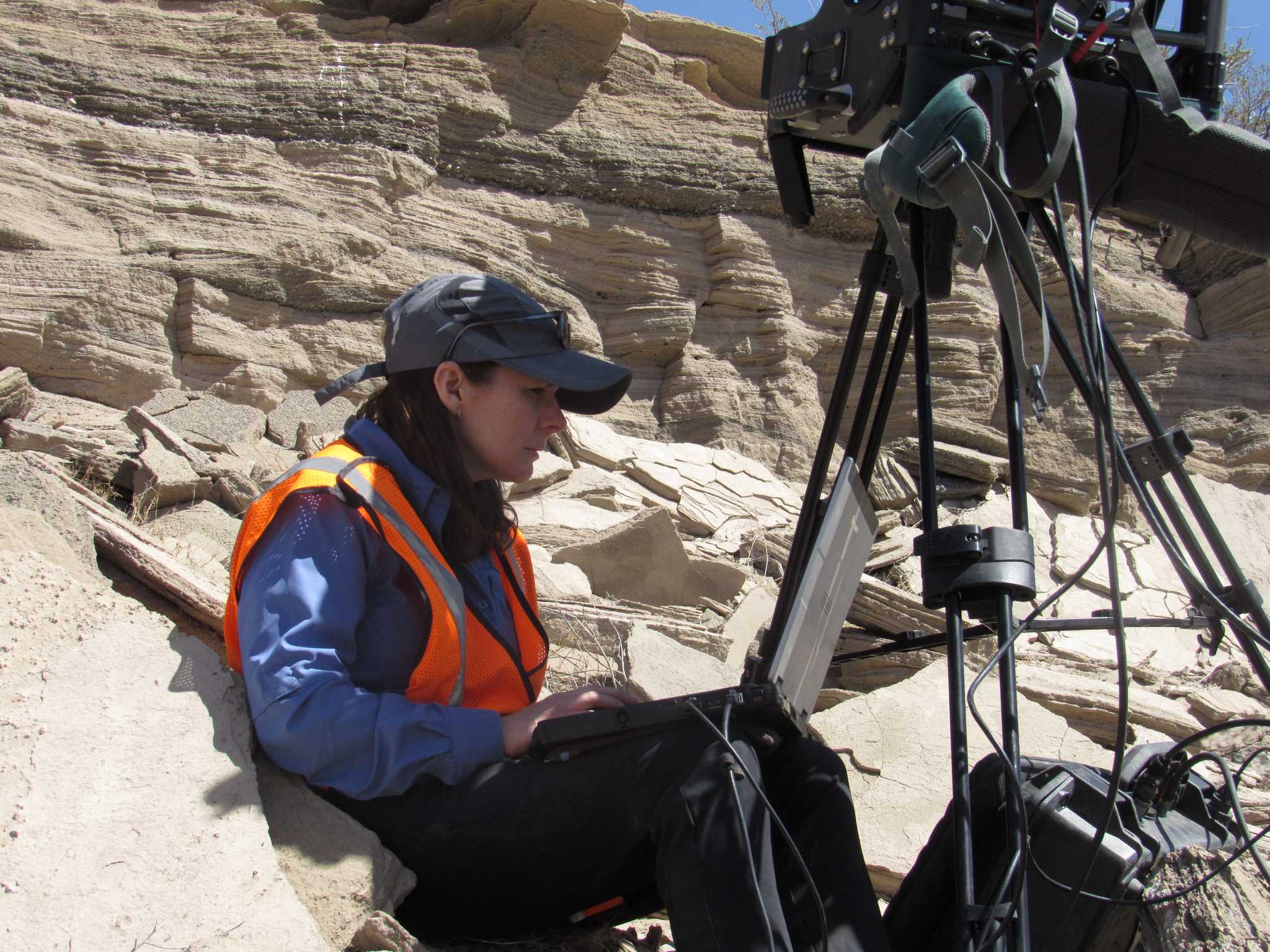

Rogers sat for hours under the hot sun in a crater called Hunt’s Hole waiting for the best moment to engage her hyperspectral imager with the outcrop across a rock field. SBU geochemistry and planetary science graduate student Reed Hopkins stood close by, assisting with adjustments to the instrument during the weeklong excursion to Hunt’s Hole and Kilbourne Hole.

The machine scans the surface of rock formations and spits out data showing a sample’s chemical composition. Knowing what’s out there on a planet could be useful to the explorers who NASA hopes to launch back to the Moon as part of the Artemis Project, in 2025. The RISE2 project is placing teams of scientists in research sites around the world like Potrillo, called analogs, to support the Artemis mission.

The work Rogers does in Potrillo is similar to what she did as a graduate student at Arizona State University. At ASU, Rogers completed her dissertation on the global variation of rock composition of Mars using satellite data, which is similar to the datasets that she is acquiring for the RISE2 mission. At SBU, she runs the Earth and Planetary Remote Sensing Lab at the university's Center for Planetary Exploration.

Rogers is a highly respected member of the geosciences field, authoring scholarly papers and serving on several NASA projects and a sought-after expert for journalists seeking to help the public understand scientific innovations and phenomena.

Her interest in science began at a young age, specifically in planetary sciences. As she got older she unintentionally distanced herself from that interest and went into college majoring in English. But she ultimately ended up switching her major after taking a geology course.

The secret to her success? She said that in order to be successful in the field you have to work hard, do good work, and have confidence in your work. But, she added, sometimes pure luck plays a role: meeting the right person at the right time, for example.

But she cautioned to never expect things to work out just because of connections someone may have.

Some challenges that Rogers faces as a geologist can range from equipment malfunctioning, which can take months to troubleshoot, or coming up with research questions and going through the process of writing up grants.

Even being a woman has had an impact on her career. She said that while she had a strong group of mentors throughout her career, which made a positive difference for her, she said she may have been excluded from a few conversations because she is a woman.

Rogers’ favorite part of being a geologist is being out in the field and working with colleagues. Only half-jokingly, she said that geologists tend to be “down to Earth.” Get it?

But she also enjoys the daily variability of her roles as a professor and scientist – whether talking with students, teaching, or analyzing data in her office.

Rogers enjoys the academic side of geology as well being out in the field, but the administrative work that comes along with academia puts a damper on it, she said.

She tries to clear up misconceptions people may have about geology not being a technical field, which it is, and with many moving parts: chemistry, physics, and biology. She said that a successful geologist must be well trained in those disciplines to understand all of the components of geology.

For example, she said, a state-of-the-art laboratory at the University of Maryland is doing incredible work with liquid convection of the earth's core, adding that most people would not think of geology like that.

Rogers has worked on multiple other projects with NASA and is the principal investigator for multiple NASA grants, mainly focused on Mars. She has done work on trying to understand ancient environments on Mars and the present day environment, and how Martian volcanic rocks weather.

Rogers was recently added to the Mars Science Laboratory mission after writing a grant for NASA.

She took her new hyperspectral imager instrument to the sites in Potrillo to collect more data. The April expedition was the instrument's second time out in the field (the first was in November 2021) and Rogers hopes to take it out to other field sites where both terrestrial and Martian geology can be researched.

A colleague on the Potrillo expedition, Cherie Achilles, said Rogers is a giant in the field, adding that she looks forward to integrating her data with what Roigers produces.

“I have friends who've worked with her over the years,” said Achilles, a NASA scientist based at Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland – who used to read Rogers’ work when Achilles was a graduate student. “She’s the best person to work with. She really knows her stuff.”

© 2025 ReportingRISE. All rights reserved.